Our Partners

Member Login

Calendar

Museum of Human Rights, Freedom and Tolerance is proud to present the article below, written by Dr. Ilya Altman and Maria Gileva of the Russian Research and Educational Holocaust Center in commemoration of the Elbe Day – April 25, 1945, when Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River in Germany.

On April 25, 2020, representatives from the USA and Russia were to meet in Torgau, Germany to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Allied victory over the German Army at the Elbe River. The joy that the Soviet troops felt upon meeting their brothers-in-arms from the West, in 1945, was mirrored by the American troops. Their delight was evidenced in their letters home and the articles they wrote for their homeland presses, which you will find in the following essay.

Why do we spend time and energy recalling military events from so long ago? Most of the participants of that 1945 meeting are no longer with us. However, we do remember that these were soldiers, officers, and journalists who did not share the same language, religion, culture, or politics. Their joy came from their common humanity. Both sides fought for the same goal: defeating Nazism. They suffered, sacrificed, risked their lives, and remained resolute in the bloody battle to stop the Nazi killing machine, which destroyed millions of Jews, Roma, Slavs, and many other innocent victims of Nazism. Their victory allowed both sides to dream of an end to war, bloodshed, and hatred, and begin to recognize our shared striving for peace.

We remember because we need to keep that dream alive. We remember because we want to realize this dream. We remember because we believe it is possible to have a better world.

Igor Kotler, Gideon Frydman, MHRFT, May 2020

Translated by Amelia Wolford

Known as the "Meeting on the Elbe,” the encounter between the Red Army's First Ukrainian Front and the First United States Army thon April 25,1945, near the town of Torgau, Germany, is a memorable event in the history of World War II. It is also a deeply touching one. Among the most famous photos illustrating this event shows Lieutenant W. Robertson and Lieutenant A.S. Sylvashko smiling and hugging with the caption “East Meets West.” It is difficult to recall another event in modern history that would better symbolize the solidarity of states so different from one other, yet united at that moment for one purpose—prompt victory over Nazism.

Ilya Altman and Maria Gileva, staff of the International Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, offer some new and little-known anecdotes about the brief encounter between allies that are based on letters, diaries, photographs, and journalistic essays.

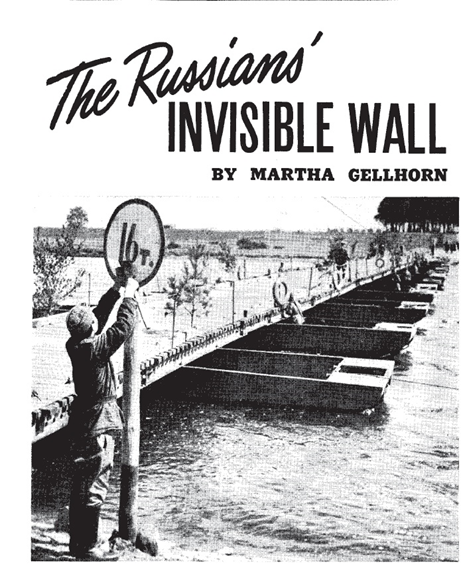

Pantoon Bridge across the Elbe. Americans and British could cross only in company of Russian officer designated to take them to a specific place for a specific purpose.

The political officer of the First Independent Guards Assault Engineering Brigade, Major of the Guards Daniil Pogulyaev, who would become a professor and a famous scientist, noted in a letter to his wife dated April 27, 1945: “Today is a great joy for all of us—Red Army troops have joined with the Allies. For this occasion, I decided to send you a bouquet of flowers (on the postcard).” Sergeant of the Guards Efim Grinkrug wrote to the famous front-line photographer David Minsker on April 28: “The War in Europe will soon be over. Everyone thinks so, and I do too. I would love to chatter more in English, tell them about everything."

In the same vein, Sergeant of the Guards Zinovii Sheinin addressed his parents and sister on May 1, 1945. He writes: "In my last letter I wrote up till the penetration of the Neisse River. Since that time, a lot has changed in the final defeat of the enemy. We crossed the Spree River, and on Apr. 26 we went to the Elbe River. There we met with our allies and friends of the First Ukrainian Front. The meeting was very warm, it is just that almost no one knew English, although they knew German relatively well and could say some things. Sister was needed in this situation." […] And now I am in Berlin, the city of murderers and full-blown fascism. Yesterday the Victory Banner was raised over the Reichstag. I wrote in my previous letter that I hoped we would meet the allies before the letter reached you, and now I hope that the world of freedom loving nations will celebrate final victory before this letter reaches you."

In those days, the American press described the historic meeting with the Red Army troops in detail. For many American soldiers and our troops, it was their first experience communicating with each other face-to-face. Even the language barrier could not stop their mutual desire to get acquainted. Translation difficulties, often turning into comical situations, were captured in American media. For example, there was an article titled, “The War in Europe Is Coming to an End” in the May 7, 1945 issue of one of the most popular magazines in the US—Life. In the two page spread, among other photos, three smiling young people are depicted with the original caption: "A Russian member of the Women's Auxiliary Corps” showed a US Lieutenant and a Red Army soldier trying to communicate. One Russian, in broken English, called everyone present “my dear.” When an American soldier attempted to buy the insignia off the cap of a Russian officer, however, he received a thunderous tirade against capitalism.

The next photo depicts a table of soldiers with happy faces—among them is war correspondent Ann Stringer, who, as indicated in the caption of the photo, “became the first American girl the Russians ever met.” It was Ann Stringer who, as a reporter for United Press, relayed to the US the first report on the meeting between allies at the Elbe River. Nine months prior to this, her husband, a Reuters correspondent, died during the liberation of Paris. Ann Stringer took part in the liberation of Buchenwald and Dachau along with American troops, and she covered the Nuremberg trials after the war.

As her biographer notes, in those days, reporters mainly amused themselves with riding jeeps, drinking champagne, and not even thinking about competition, because they thought everyone was celebrating the approaching victory together. However, Anne Stringer persuaded her friends in American intelligence to provide her with a cargo plane with a pilot who took her to Torgau. She happened to notice a man there with a boat and asked him to row her to the other side. Thus, she became the first American reporter who met Soviet troops on the Elbe River.

Many, many toasts in vodka, with which the Russians were lavish hosts, wine and captured cognac are drunk by Soviet and U.S. troops and officers who mingled, heedless of rank. Correspondent Ann Stringer (above) was the first American girl most of the Russians had seen.

Martha Gellhorn, a legendary war correspondent, was another significant female participant in the "Meeting on the Elbe." The third wife of Ernest Hemingway, she was with him in Spain as a correspondent, and he dedicated one of his greatest novels—For Whom the Bell Tolls—to her. Because of her constant travels, however, he demanded that she choose between him and her profession. Martha divorced him just weeks prior to the end of the war.

She also experienced the liberation of Dachau. But it is rare to read about her feelings on the meeting with the Red Army in biographical essays about her. Meanwhile, she covered it in detail in her article ironically titled "The Russians’ Invisible Wall" for the June 30, 1945 issue of the American magazine Collier's Weekly:

There was one Russian guard standing on the ponton [sic] bridge on our side of the Elbe. He was small and shaggy and bright-eyed. He waved to us to stop and came over to the jeep and spoke Russian very fast, smiling all the time. Then he shook hands and said, ‘Americans?’ [Amerikanski?—author’s note] Then he shook hands again, and we saluted each other. A silence followed, during which we all smiled. I tried German, French, Spanish and English in that order: We wanted to cross the Elbe to the Russian side and pay a visit to our allies. None of these languages worked. The Russians speak Russian. The G.I. driver now made a few remarks in Russian which filled me with wonder and admiration. "How did you ever learn?" I asked. "You got to talk a little bit of everything to get around these days," he said modestly. The Russian guard had listened and digested our request and he now answered. The operative word in his answer was: no [“niet”—author’s note]. It is the only word in Russian I know but you hear it a lot, and afterward there is no use arguing. Martha, in her characteristic ironic manner, describes a few of such dialogs with other Red Army soldiers who made attempts to sneak to the other shore. In the end, they met with a certain colonel (name withheld), who invited them to the table. “Then we began to talk about crossing the Elbe. It appeared that the colonel had not understood my request; no, it would be impossible to go unless the general gave his permission. Then could he telephone the general? What? Now? Yes, now. "Time is money," said the interpreter sagely. "Oh, hell!" said I, not so sagely. "You are in such a hurry," said the colonel. "We will talk this all over later." "You do not understand," I said. "I am a wage slave. I work for a bunch of capitalist ogres in New York who drive me night and day and give me no rest. I will be severely punished if I hang around here eating with your citizens when it is my duty to my country to cross the Elbe and salute our gallant allies."

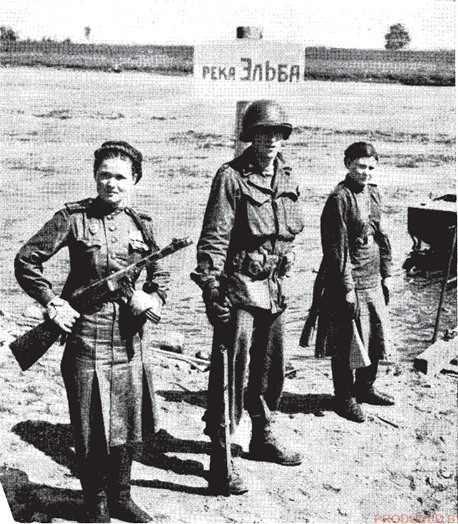

Russian woman officer, U.S. lieutenant and Red soldier try to converse despite their linguistic difficulties. One Russian with a smattering of English called everyone "my dear". But when a GI tried to buy a Russian officer's cap insignia, he got instead a thundering tirade against capitalism.

Waiting for the call to the general, Martha talked with other Red Army soldiers. A modest lunch spilled over into conversations about Russia and questions about what Martha thought about the Red Army: “I would give anything to see it, but in the meantime I thought it was wonderful—the whole world thought it was wonderful.”

Commemorative events were held after the end of the war. Only in 1985, however, did our veterans participate in one of them. In October 2019, an open letter from the Organizing Committee of the Elbe River Meeting Ceremony was published in The Washington Times. It invited U.S. President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin to attend the commemorative meeting in Torgau on April 25, 2020. The Committee also sought their support for holding the meeting, since "The upcoming anniversary may be the last for many of the remaining veterans and witnesses of that tremendous event.”

The spirit of this truly historic event in 1945 was immortalized in a solemn toast given by the participants that became known as the Oath of Elba. There is no official text of it. Only the diary of Joseph Polowsky, an American soldier and son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, preserved its words and atmosphere.

"At this historic moment of the meeting of nations, all of the soldiers present—ordinary soldiers, Americans and Russians—solemnly swore that they would do everything in their power to prevent such things from ever happening in the world again. We pledged that the nations of the world would and must live in peace. This was our Oath of Elbe… It was a very informal, but solemn moment. There were tears in the eyes of most of us. Perhaps a sense of foreboding that things might not be as perfect in the future as we anticipated. We embraced. We swore never to forget.”

Russian policewomen, Karuma Galemua, left (who has 42 Germans to her credit), and Vera Soeddovuik, stand guard with Pfc. E. O'Donaghue, of Sacramento, Cal.

Paratrooper Vasilii Poleev from Volgograd shared his impressions of the meeting with his mother and grandmother in a letter written at the end of April 1945: “Well, of course, the most joyful moment for a soldier on the front-line is meeting his brothers-in-arms. Imagine what our meeting with the Americans was like. As soon as our soldiers began converging with the Americans, thousands of multicolored missiles flew in the air. We were embracing, kissing, and congratulating each other on the victory.”

And this is how the famous poet Konstantin Simonov describes the meeting in his April 28, 1945 article for Тhe Red Star:

“The great brotherhood in arms was not born today, and not yesterday. It was born long ago: on the banks of the Dnieper, the Vistula, and the harsh Norman coast. But today, perhaps, for the first time it is so clear. Today, for the first time, Soviet and American officers are walking alongside each other on German soil. Cameramen are filming our officers in Russian army caps and service shirts. Insignias and Stalingrad medals tell the story of the long and difficult path of war, and next to those insignias, familiar American ribbons and British insignias can be seen on some of our officers—another testimony to the brotherhood in arms. Cameramen film the gray-green steel helmets of the Americans, their simple, loose khaki uniforms, their modest epaulettes with silver stars and squares. […]

—How they waited, how they waited for this meeting! —tells me a TASS correspondent, who spent eight months in the American Army and today, after a long time apart, met with his fellow countryman for the first time.

The 2020 pandemic interrupted all plans for a ceremony commemorating the event. At the end of April 1945, however, thousands of our countrymen and allies rejoiced in the forthcoming victory over the Nazis and their swift return home. They were crying, embracing, and making plans for the future. Victory was only days away.

Publication prepared by Maria Gileva and Ilya Altman